By Middle East Technical University (METU) – Institute of Marine Sciences (IMS)

Harbour construction endangering a known Mediterranean monk seal breeding cave in Yeşilovacik, Mersin, poses great danger to the northeastern population of the species

Online Petition: Please consider signing the online petition against this development at Change.org

The Middle East Technical University Institute of Marine Sciences (IMS-METU) has been studying the Mediterranean monk seal population inhabiting the northeastern Mediterranean since 1994. The cave surveys and subsequent monitoring activities in the area showed that the western rocky shores of Mersin (a county on the south coast of Turkey) holds the largest continuously breeding monk seal colony on the Turkish coast. During the onset of the 1990’s, this group of seals was on the verge of extinction because the social bonds within the colony had been broken by very high deliberate killings and loss of habitat. The fragmented community structure led to almost zero whelping rate. However, until very recently, despite the negative growth of the species elsewhere in the Mediterranean, the number of seals in this area was increasing with steadily improving whelping success. The size of the colony is estimated as 34 individuals as of 2013. Yet, the range of this population was expanded by some members of the colony returning to habitats abandoned in the past and establishing new families.

The plight of the species in the area was probably reversed by two conservation measures enforced since 1997. The first is the ban on an industrial fishery over the seals’ overfished feeding habitats by which the main food source of the growing colony was secured. Secondly, the coastal strips containing essential habitats for seals, such as breeding and resting caves, have been designated as a First Degree Natural Asset, so that further coastal development has been stopped. These regulations enabled re-integration of the dispersed seal community so that social structure within the families was re-established and the breeding success was re-gained.

A pregnant seal requires certain morphological features in a cave in order to use it to give birth and to raise her pup, such as an underwater entrance reaching to a well aerated air chamber; a haul-out platform long and wide enough to protect a new born pup against high waves during storms; a well sheltered inner pool in which the land-born pup can practice swimming. There are more than 50 caves used by the seals within the protected area; however only 8 of these caves fulfil the whelping requirements allowing them to be used by breeding females. This low number clearly underlines the uniqueness of the breeding caves and urges their protection.

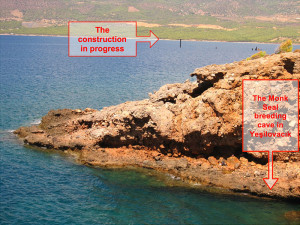

One of these breeding caves is located near to Yesilovacık village. The cave has been monitored remotely by infrared cameras and it was documented that a small family of seals composed of 4 individuals use the cave throughout a year. This cave marked the easternmost limit of the seal colony before enforcement of the seal conservation measures mentioned above. Today this cave acts as a bridge between the core colony and the pioneers moving further east. Moreover, it is a very critical cave since there are no other caves in the near vicinity with similar morphology that the inhabitants could move to if they are forced to leave. Very recently the university was contacted to evaluate a modification plan on the borders of one of the Natural Assets mentioned above. The plan involves construction of a new road passing through the protected area on land. Further inspections revealed that the road is just the tip of the iceberg; and that the actual plan is to construct a huge marine terminal just 500 meters away from a breeding cave and the road was intended to provide a shortcut between the new harbor and the main arterial road for the expected lorry traffic of 400 vehicles per day. The local authorities for the protection of the Natural Assets did not permit construction of the new road. However by law, the “Natural assets” conservation status does not cover seaward extension of an ecologically important coastal structure. Such a massive construction in the sea, which involves the transport and dumping of huge quantities of construction material, and the subsequent marine traffic, would inevitably have a detrimental impact on the seal cave and its inhabitants. Moreover, with the impact of a new nuclear power plant, that will be constructed 10 km west of the marine terminal, the entire monk seal population in the north-eastern Mediterranean would be deeply impacted. It is feared that these new constructions will return the seal population to the fragmented ill state experienced in early 1990’s.

As such projects would undoubtedly have detrimental consequences on the seals, a scientific team of experts from IMS-METU, has been extremely concerned about the entire venture and therefore the team initiated a monitoring survey in the cave using photo-traps on 4th April 2010 (ca 900 seal photographs have been obtained to date). Based on the surveys carried out at the site, the national authorities in charge of monk seal conservation were alerted on the importance of this issue. The inevitable consequences of the construction and chiefly the crucial loss of yet another breeding cave for the seal population in the entire eastern Mediterranean has been presented to the authorities concerned by various means including population viability analysis which projects a hopeless future for the colony. Following the reckless reaction by the authorities, a letter of complaint was submitted to the secretariat of the BERN Convention. Additionally as a response to the situation, the NGO Underwater Research Society issued a summons against the ministry responsible for the protection of wildlife in Turkey for reaching a critical decision based on a superficial report and disregarding the environmental significance of the site. Later, the ministry stated that no construction will begin until the National court has reached its final decision.

According to the report submitted by the Turkish government to the Standing Committee of the BERN Convention in October 2013, Turkish authorities halted construction for only five months despite the previous decision that “there will be no construction until the National court has reached a final decision” but meanwhile commencement of the construction operation was tragically witnessed. It was recently stated in the report of the Standing Committee held on 3-6 December 2013, that Turkish authorities will establish a pool of experts to inspect the current situation and that meanwhile building construction be suspended until the possible impact on the morphology of the cave and consequently on the Monk Seal population are assessed.

The research team has visited the area on a regular basis and is in contact with the local village inhabitants at the construction site. They witnessed that the construction activities carried on (with some deceptive slowdowns) in the area even during the breeding season of the monk seal. The efforts to push the authorities to take necessary actions and to stop the construction until the court’s decision have so far proven unsuccessful. It is vitally important to emphasize that, since the huge building construction project is continuing and has recently progressed extremely rapidly then in all probability construction may be finalized before the national court reaches its final decision.

Current Situation

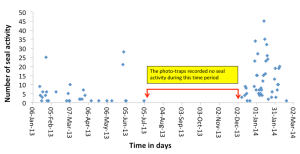

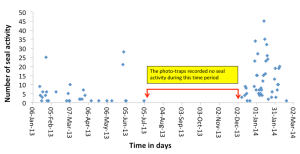

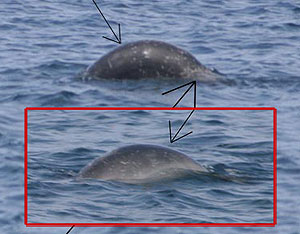

Given that all cameras were active and recording the seal movements in the cave since the very beginning there has been a remarkable and worrying decrease in seal activity in the cave during 2013. More strikingly no single event was recorded during the period from the beginning of July 2013 until the beginning of December 2013. Recordings obtained in December 2013 show one female – presumably the mother – and one new born pup photographed in the same cave. Another cause for much concern has been the disappearance of a pup born in December 2012. Typical to the monk seals in the eastern Mediterranean, a young seal tends to remain in and around the natal cave during the first year of life. Moreover the number of seals that previously used the cave before the initiation of construction has vanished. There are already very few caves in the region suitable for breeding activity which is considered to be a critical factor limiting the breeding success. The lack of seal activity in the cave for the past 6 months (Fig 1) clearly shows that the seals abandoned the cave and most probably the entire area during the heavy construction period. However, the female carrying the pup was forced to return to the cave as there was no other alternative whelping site in the immediate surroundings. The last record obtained from the cameras was a single photograph showing the new born pup in a very undernourished and weak condition.

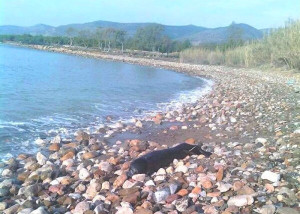

Unfortunately, the most disturbing event was the death of the said pup born in the cave around 24 November 2013. The carcass of the animal was found on the beach near the construction site by local inhabitants on 28th February 2014. A group from the construction company personnel allegedly attempted to dispose of the carcass as reported by the locals. Due to this threat, the locals hid the carcass with the aim of delivering it to IMS-METU for examination.

The necropsy of the pup was performed on 29th February 2014 at IMS-METU by authorized veterinarians. Examination revealed clear indications of malnutrition such as extremely thin blubber (1.9 cm), an empty gut with a very cachectic appearance and state. Furthermore, inspection of the events recorded by the photo-traps show no signs of the mother visiting the cave, indicating that the mother-pup bond had been broken. In the extensive and uninterrupted series of photographs the pup continually rests on the shore inside the cave, does not leave the cave in search of food and is neither accompanied by his mother nor breastfed.

To help, please sign the petition at Change.org.

Turkey

![]() Alexandros A. Karamanlidis, P. Jeff Curtis, Amy C. Hirons, Marianna Psaradellis, Panagiotis Dendrinos and John B. Hopkins III. 2014. Stable isotopes confirm a coastal diet for critically endangered Mediterranean monk seals. Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10256016.2014.931845.

Alexandros A. Karamanlidis, P. Jeff Curtis, Amy C. Hirons, Marianna Psaradellis, Panagiotis Dendrinos and John B. Hopkins III. 2014. Stable isotopes confirm a coastal diet for critically endangered Mediterranean monk seals. Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10256016.2014.931845.

Orphaned monk seal pup ‘Artemis’ has been found dead on Skiathos in the Northern Sporades.

Orphaned monk seal pup ‘Artemis’ has been found dead on Skiathos in the Northern Sporades.