by Aylin Akkaya Bas*, Nicola Piludu, João Lagoa and Elizabeth Atchoi, Marine Mammals Research Association, Antalya, Turkey**

Introduction

Mediterranean monk seals (Hermann, 1779) were once widely and continuously distributed in the Mediterranean Sea, Black Sea and North Atlantic waters (Aguilar 1999). The species is considered to be one of the world’s most endangered pinnipeds, with the global population estimated to be around 500 individuals (Karamanlidis & Dendrinos 2015), only 50-100 of which are left in Turkey (Güçlüsoy et al. 2004; Öztürk et al. 1991). Antalya Bay is subjected to high marine traffic year-round, and especially during summer months, when tourism activities peak. We report the most recent sightings of Mediterranean monk seals in Antalya Bay and investigate the impact of boat traffic on the species. Considering that the population in the Turkish Mediterranean is estimated at around 40 individuals (Güçlüsoy et al., 2004), the recent sightings in Antalya are of vital importance for the knowledge of the overall Turkish population, and provide great insight for conservation plans and consequently for the species’ survival in the region.

Mediterranean monk seals (Hermann, 1779) were once widely and continuously distributed in the Mediterranean Sea, Black Sea and North Atlantic waters (Aguilar 1999). The species is considered to be one of the world’s most endangered pinnipeds, with the global population estimated to be around 500 individuals (Karamanlidis & Dendrinos 2015), only 50-100 of which are left in Turkey (Güçlüsoy et al. 2004; Öztürk et al. 1991). Antalya Bay is subjected to high marine traffic year-round, and especially during summer months, when tourism activities peak. We report the most recent sightings of Mediterranean monk seals in Antalya Bay and investigate the impact of boat traffic on the species. Considering that the population in the Turkish Mediterranean is estimated at around 40 individuals (Güçlüsoy et al., 2004), the recent sightings in Antalya are of vital importance for the knowledge of the overall Turkish population, and provide great insight for conservation plans and consequently for the species’ survival in the region.

Methodology

Systematic surveys were carried out from 1st of March to 29th of December 2015 from two independent observation stations located on the coastal cliffs of Antalya, covering approximately 300 km2 of sea. The geographic position and activity of boats and seals were recorded using a FOIF theodolite paired with a laptop and later plotted via ArcGIS v.9. Group size, behaviour, diving interval, and proximity of boats to seals were recorded. Behavioural states were defined following Pires (2011) as travelling, predation, resting and socializing.

Results

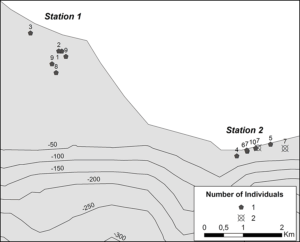

In total, surveys were conducted for 84 days (360 hours). Mediterranean monk seals were sighted on thirteen different days and were observed for a total of 4.42 hours. Two independent sightings were recorded in Olympos, Antalya on the 28th September 2015 and 9th June 2016 by a local diver (Table 1, Figure 1). September had the highest encounter rate with four sightings; seals were not sighted in March, October, November and December. 75% of the sightings took place during morning hours (between 06:00 – 10:00) with the latest sighting at 14:46. Sightings were close to the coast, with the furthest sighting occurring 400 m from the closest shore, and all in waters of depths of 50 m or less. Observation duration ranged from 5 seconds to 2.14 hours. Diving intervals were recorded in four of the sightings and the average dive time was 8.4 minutes (n=15, SD=6). All sightings were of single individuals, except on one occasion (28th August 2015), when two different mother/pup pairs were sighted simultaneously. Sighted individuals most often engaged in travelling and predation behaviour, each covering 46% of recorded behaviours. Resting behaviour was only recorded in 8% of the observation time.

In total, surveys were conducted for 84 days (360 hours). Mediterranean monk seals were sighted on thirteen different days and were observed for a total of 4.42 hours. Two independent sightings were recorded in Olympos, Antalya on the 28th September 2015 and 9th June 2016 by a local diver (Table 1, Figure 1). September had the highest encounter rate with four sightings; seals were not sighted in March, October, November and December. 75% of the sightings took place during morning hours (between 06:00 – 10:00) with the latest sighting at 14:46. Sightings were close to the coast, with the furthest sighting occurring 400 m from the closest shore, and all in waters of depths of 50 m or less. Observation duration ranged from 5 seconds to 2.14 hours. Diving intervals were recorded in four of the sightings and the average dive time was 8.4 minutes (n=15, SD=6). All sightings were of single individuals, except on one occasion (28th August 2015), when two different mother/pup pairs were sighted simultaneously. Sighted individuals most often engaged in travelling and predation behaviour, each covering 46% of recorded behaviours. Resting behaviour was only recorded in 8% of the observation time.

Table 1. List of Mediterranean monk seal sightings in Antalya Bay, Turkey (Group n = Number of groups; Ind., n = Number of individuals).

| Obser-vation Order | Date | Grp. n | Ind. n | Coordinates | Duration of Observation | Observer Type | |

| Latitude | Longitude | ||||||

| 1 | 06.04.15 | 1 | 1 | 36,868358 | 30,717608 | 00:00:30 | Researcher |

| 2 | 03.06.15 | 1 | 1 | 36,868399 | 30,716916 | 00:00:30 | Researcher |

| 3 | 09.06.15 | 1 | 1 | 36,872549 | 30,710370 | 00:19:23 | Researcher |

| 4 | 14.07.15 | 1 | 1 | 36,844051 | 30,758193 | 00:50:00 | Researcher |

| 5 | 21.07.15 | 1 | 1 | 36,846757 | 30,766002 | 00:05:00 | Researcher |

| 6 | 11.08.15 | 1 | 1 | 36,845150 | 30,760602 | 00:05:00 | Researcher |

| 7 | 28.08.15 | 2 | 2 | 36,845941 | 30,763090 | 00:04:13 | Researcher |

| 7 | 28.08.15 | 1 | 2 | 36,845782 | 30,769369 | 00:42:54 | Researcher |

| 7 | 28.08.15 | 3 | 1 | 36,845407 | 30,760500 | 00:05:54 | Researcher |

| 8 | 03.09.15 | 1 | 1 | 36,863364 | 30,716302 | 00:05:00 | Researcher |

| 9 | 17.09.15 | 1 | 1 | 36,865397 | 30,715356 | 02:14:37 | Researcher |

| 9 | 17.09.15 | 2 | 1 | 36,867132 | 30,718574 | 00:00:30 | Researcher |

| 10 | 24.09.15 | 1 | 1 | 36,845844 | 30,762567 | 00:00:30 | Researcher |

| 11 | 28.09.15 | 1 | 1 | 36,389119 | 30,496578 | 00:05:00 | Diver |

| 12 | 09.06.16 | 1 | 1 | 36,387446 | 30,487483 | 00:10:00 | Diver |

| 13 | 13.06.16 | 1 | 1 | 36,846990 | 30,768247 | 00:00:60 | Researcher |

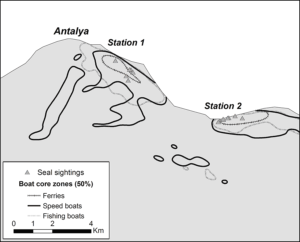

An average of 87 boats was present every day within the survey area (51% tour boats, 26% fishing boats and 20% speedboats). When the core zones for boats and seals were mapped there was considerable overlap (Figure 2). Additionally, boats were recorded within a 400 m radius from the focal seal in 31% of the observation time. Both possible active avoidance behaviour (i.e. leaving the area permanently) and possible habituation (i.e. resurfacing in similar area within a time interval), were recorded towards the speedboats. No signs of avoidance to nearby fishing boats were recorded.

Discussion

The continued presence of adults throughout the study period, and the single observation of two pups simultaneously, suggest that a population of Mediterranean monk seals still survives in Antalya Bay. If appropriate conservation measures are taken, population growth can be achieved, especially given the proximity of the study site to the Olympos-Beydağları National Park, a critical site for the species (Gücü et al. 2009). However, in the current situation, the bay is still characterised by high human activity that might prevent the survival of a healthy colony. Given the observation of mother/pup pairs, and based on informal talks with locals who have a personal interest in marine life and claim to check often on specific caves in order to see seals with their pups, we conclude that despite heavy human presence there is at least one breeding cave in Lara Cliffs.

Our study showed overlap between area usage by seals and boats. Seals were spotted predominantly during early morning hours, when most boats are still absent, which could be an indication of intentional avoidance of boats. Without further research, however, no definitive cause can be deduced. No direct avoidance was recorded towards fishing boats, again suggesting some degree of habituation. This is in accordance with the species’ opportunistic feeding behaviour (Johnson & Karamanlidis 2000). Fishermen have reported seals following their fishing boats for long periods of time and actively waiting in specific areas for fishermen to set their nets (Johnson & Karamanlidis 2000). These interactions with artisanal and industrial fisheries, however, are likely to be a source of stress, ultimately causing a direct threat to the population of Mediterranean monk seals. It is known that various methods (i.e. lights, chasing seals with boats, noise and warning shots with rifles) are used by fishermen to keep seals away from the nets (Danyer et al. 2013; Güçlüsoy & Savaş 2003). Direct persecution and deliberate killing have also been reported in Turkey (Danyer et al. 2013; Güçlüsoy et al. 2004; Öztürk 2007).

The conflict between human activities and seals should be addressed by an array of diverse actions that should combine research, education and enforcement. The establishment of protected areas has been proven effective to some degree (Pires et al. 2008). Fishermen and boat crews should be engaged in each conservation activity in order to attempt perception change and avoid the resulting possible local extinction of the species.

Our results demonstrate the pressing urgency to continue and update the research programme to investigate Antalya’s population. Obtaining robust data on species distribution, individual identification, and especially confirming the presence of seal caves and pupping areas are the first steps in developing conservation measures that will encourage the survival of Antalya’s population of Mediterranean monk seals. While local efforts to preserve a possible Antalya colony are critical, a nationwide initiative aimed at mapping the remaining colonies and creating a network of marine protected areas connected by corridors, alongside educational and awareness programs, remains the highest priority to ensure the survival of the species in Turkey.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank all the volunteers, Alec Christie, Anissa Belhadjer, Ayça Eleman, Callum Duffield, Carine Gansen, Dawid Szubryt, Henry Appleton, Jesse Poot, Johanna Bergman, Nicole Tomsett, Petra Solarik, and Sarah Bellamy, who helped throughout the process of collecting data, and the Marine Mammals Research Association for financial support.

References

Aguilar, A. 1999. Status of Mediterranean monk seal populations. In RAC-SPA, United Nations Environment Program, pp. 1-60. Aloès Edition, Tunisia.

Danyer, E., Özbek, E.Ö., Aytemiz, I. & A.M. Tonay. 2013. Preliminary report of a stranding case of Mediterranean monk seal Monachus monachus (Hermann, 1779) on Antalya coast, Turkey, April 2013. Journal of the Black Sea/Mediterranean Environment, 19: 278˗282.

Güçlüsoy, H, & Savaş, Y. 2003. Interaction between monk seals Monachus monachus (Hermann, 1779) and marine fish farms in the Turkish Aegean and management of the problem. Aquaculture Research, 34: 777-783.

Güçlüsoy, H., Kıraç, C.O, Veryeri, N.O. & Savaş, Y. 2004. Status of the Mediterranean monk seal, Monachus monachus (Hermann, 1779) in the coastal waters of Turkey. Journal of Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences, 21: 201–210.

Gücü, A. C., Sakinan, S. & Meltem, O. 2009. Occurrence of the critically endangered Mediterranean Monk Seal, Monachus monachus, at Olympos-Beydağları National Park, Turkey (Mammalia: Phocidae). Zoology in the Middle East, 46: 3-8.

Johnson, W.M. & Karamanlidis A.A. 2000. When fishermen save seals. The Monachus Guardian, 3: 18-22.

Karamanlidis, A. & Dendrinos, P. 2015. Monachus monachus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.2. Http://www.iucnredlist.org. [Accessed 25 July 2015].

Öztürk, B. 2007. Akdeniz Foku ve Korunmasi. Yalıkavak Environment and Seal Research Society Publication no: 1. Muğla, Turkey.

Öztürk, B., Candan, A. & Erk, M.H. 1991. Cruise results covering the period from 1987 to 1991 on the Mediterranean Monk Seal (Monachus monachus Hermann, 1779) occurring along the Turkish coastline. In Conservation of the Mediterranean Monk Seal -Technical Aspects. Antalya, Turkey.

Pires, R. 2011. Monk Seals of the Archipelago of Madeira. Serviço do Parque Natural da Madeira. Funchal, Portugal.

Pires, R., Neves, H.C. & Karamanlidis, A.A. 2008. The critically endangered Mediterranean monk seal Monachus monachus in the archipelago of Madeira: Priorities for conservation. Oryx, 42: 278-285.

*Corresponding author: akkayaaylinn@gmail.com

**Marine Mammals Research Association, Kuskavagi Mah. 543 Sok. No.6/D Dükkan, 07070, Antalya, Turkey.

I appreciate your efforts to study and save this species. I regularly check this site for new information about these wonderful seals. I will pray the local fishermen in and around Antalya will stop harming the seals. The fish must be shared by all. I keep an eye towards their kinfolk in the Hawaiian Islands. Mankind needs to be ‘kind’ to these wonderful sea dogs.

Sincerely, Jeff in Atlanta, GA, USA.

I saw 2 large seals swimming towards a rock id swam out to at approximately 19:00 . I was flabbergasted at their size & beauty as they came within a metre of where I was sitting . I was worried I was on their favorite rock as it was quite secluded & extremely small & very close to a much larger rock that had steep sides so it was pretty well protected from sight on the steep cliffs .

It is my favourite place in the whole world to swim & sit for hours being splashed by the sea .

I usually dive off if the waves get bigger , often its because a large boat is approaching.

Only today i was amazed to see the seals swimming behind me as I was swimming back !!! Not too close but close enough to make today one of the best experiences of my life.. Amazing creatures & i cant wait for tomorrow even more now .