Judge issues ruling in “monk seal starvation” case

The critically-endangered Hawaiian monk seal won protection from a Federal court on 20 November, following a judge’s ruling that the National Marine Fisheries Service is violating the Endangered Species Act and National Environmental Policy Act.

In issuing a ruling in a case brought by the Earthjustice Legal Defense Fund on behalf of three environmental groups, Federal District Court Judge Samuel King found that NMFS is illegally failing to protect the Hawaiian monk seal from the impacts of two local fisheries.

The ruling was handed down despite NMFS’ efforts to avoid a preliminary injunction, and legal condemnation of a policy that has long been implicated in the starvation of Hawaiian monk seals in the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge [see NMFS ducks judgement, TMG 3(2): November 2000]. NMFS’ earlier commitment to impose a moratorium on lobster fishing in the Northwest Hawaiian Islands was apparently deemed inadequate by Judge King.

In his ruling, Judge King found both the lobster fishery and a segment of the bottomfish fishery to be in violation of the Endangered Species Act and National Environmental Policy Act. He issued an injunction halting the lobster fishery until NMFS completes an analysis of its impact on the monk seals under the Endangered Species Act. NMFS was also ordered to complete an environmental impact statement.

The largest monk seal breeding colony at French Frigate Shoals, the court heard, declined by 55 percent during the 1990s, with juvenile seals starving because of lack of available prey.

Foraging Hawaiian monk seal

Judge King also ruled that NMFS had been violating the Endangered Species Act by permitting the bottomfish fishery to operate regardless of its impact on the Hawaiian monk seal. Evidence was presented implicating the industry in hooking seals, feeding seals unwanted fish containing ciguatera toxin, and even bludgeoning monk seals. Despite such evidence, NMFS had made no effort to station observers on bottomfish fishing boats.

The plaintiffs in the case – Greenpeace, the Center for Biological Diversity and the Turtle Island Restoration Network – expressed satisfaction with the ruling. Finding particular praise among the plaintiffs was Judge King’s implicit insistence that the precautionary principle be applied by NMFS in justifying fishing activity in the area. With detailed impact assessments now required by the court, plaintiffs expressed the view that NMFS would no longer be able to profess ignorance of environmental impacts for the sake of economic interests.

The full text of the Court’s finding is available for download in the Monachus Library:

United States District Court. 2000. Order granting in part and denying in part plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgement, granting in part and denying in part defendants’ cross-motion for summary judgement, and granting in part plaintiffs’ motion for a permanent injunction. 15 November 2000: 1-43.

Further reading

ENS. 2000. Hawaiian judge halts lobster fishery to benefit monk seals. Environmental News Service, 20 November 2000. [Available in the Monachus Library].

Johnson, W.M. 1999. The old woman who swallowed the fly. The Monachus Guardian 2(1): May 1999.

Lavigne, D.M. 1999. The Hawaiian Monk Seal: Management of an Endangered Species. Pages 246-266 in J.R. Twiss Jr. and R.R. Reeves (eds.). Conservation and Management of Marine Mammals. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London. 471 pp.

Marine Mammal Commission. 2000. Hawaiian monk seal (Monachus schauinslandi). Pages 44-55 in Chapter III, Species of Special Concern, Annual Report to Congress, 1999. Marine Mammal Commission, Bethesda, Maryland. [Available in the Monachus Library].

NMFS ducks judgement. The Monachus Guardian 3(2): November 2000.

Ragen, T.J. & D.M. Lavigne. 1999. The Hawaiian Monk Seal: Biology of an Endangered Species. Pages 224-245 in J.R. Twiss Jr. and R.R. Reeves (eds.). Conservation and Management of Marine Mammals. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London. 471pp.

“Living rainbow” may benefit monk seals

Seeking to bolster his shaky environmental legacy, outgoing U.S. President Bill Clinton set aside a huge swathe of Hawaiian ocean by executive decree on 7 December, effectively creating a marine preserve half the size of Texas. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve, as it is officially known, is the single largest protected area ever created in the U.S., and is designed to safeguard fragile coral reef habitat along the 1,930 km (1,200 miles) Leeward chain formed by the remote Northwestern Hawaiian islands. The area, which encompasses the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge, is the principal habitat of the endangered Hawaiian monk seal (Monachus schauinslandi), which is thought to be declining by about 5% a year.

“This area is a special place where the sea is a living rainbow,” Clinton declared in his announcement, claiming that the reserve would establish a new global standard for the protection of coral reefs and marine wildlife.

According to the U.S. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the reserve officially came into being on 18 January 2001, following the required 30-day public comment period.

NOAA’s priority is now to develop the reserve’s complex operations (management) plan, and to prepare the legislative framework that will eventually designate the area as a National Marine Sanctuary.

Although the reserve surrounds Midway Atoll, it does not incorporate it. Midway is a National Wildlife Refuge, and the only island in the archipelago that permits public access. While geographically a part of the state of Hawaii, its jurisdiction falls under the auspices of the US Navy. It is currently administered in a public-private partnership involving Midway Phoenix Corp. and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

In recognition, perhaps, of administrative problems posed by the multi-layered bureaucracy, President Clinton’s Executive Order calls for “coordinated management” between the new Reserve, the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge, the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge, and the State of Hawaii.

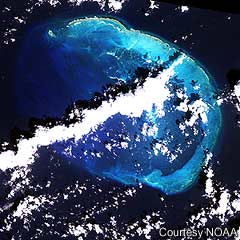

Satellite image of French Frigate Shoals

Although it is too early to judge whether the new Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve will have any tangible effect upon the conservation of the monk seal, it will spell stricter environmental controls:

- Oil, gas and mineral exploitation will be banned.

- While native Hawaiian subsistence fishing and cultural pursuits will be allowed to continue, commercial and recreational fishing will be restricted.

- Removal of coral will be prohibited.

- Dumping, dredging and anchoring over living or dead coral will be banned.

- Stricter regulations will apply in 15 special Reserve Preservation Areas.

In what might be interpreted as a rebuke to controversial National Marine Fisheries Service actions in the area – most notably the agency’s decision to maintain fishing pressure despite monk seals dying of starvation – the Presidential Executive Order clearly emphasises a commitment to the precautionary principle:

“The Reserve shall be managed using available science and applying a precautionary approach with resource protection favored when there is a lack of information regarding any given activity, to the extent not contrary to law.”

Reserve Preservation Areas, which account for some 4.8% of the entire sanctuary, are to impose stricter regulations than in other sectors. They incorporate most Hawaiian monk seal habitat in the NWHI, including Nihoa Island, Necker, French Frigate Shoals, Laysan, Lisianski, Pearl and Hermes Atoll and Kure.

However, while the Executive Order states that no commercial or recreational fishing will be permitted in the 15 Reserve Preservation Areas, there are eight exceptions. At Nihoa Island, Necker, Gardner Pinnacles, Maro Reef, Laysan, and Lisianski, it is stipulated that the controversial bottomfish fishery may continue at current levels under specific depth restrictions, pending review and comment.

Following consultations within the Reserve Council – an advisory body established to reflect diverse opinions on the conservation and management of the area – commercial and recreational fishers were reported to have gained some relief from restrictions which originally sought to cap fishing activity at current levels. As implied earlier, it remains to be seen whether the precautionary principle will be applied with the no-nonsense rigour with which it was originally intended, or whether managers will spend years fudging and redefining its meaning.

Further reading

The NOAA web site dedicated to the new reserve: Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve.

In the Monachus Library:

Federal Register. 2000. Vol. 65, No. 236. Executive Order 13178 – Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve. Thursday, December 7, 2000: 1-9.

NOAA. 2001. Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve. Overview.

NOAA. 2001. Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve. Questions and Answers.

NOAA. 2001. Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve Executive Order. Summary.

Open for comment

In a related development, on 5 January 2001 the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council released for public comment a Draft Fishery Plan (DFP) and a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) for Coral Ecosystems of the Western Pacific Region. According to an accompanying memo signed by Executive Director Kitty Simonds, the FMP proposes, among other measures, to “designate marine protected areas, including no-take reserves and areas zoned for specific fishing activities with a special permit” and to “specify the use of selective, non-destructive gears and methods for harvesting.”

The DFP, which comes in the wake of harsh judicial criticism of NMFS fisheries policy in the NWHI [see Judge issues ruling in “monk seal starvation” case, above] purports to be the first ever ecosystem-based fisheries plan developed in the United States, aiming at “sustainable use” of fragile coral ecosystems.

Implementation of the Plan is envisaged for the Western Pacific Exclusive Economic Zone, including the NWHI. It is not known, as yet, how any of the possible Marine Protected Areas discussed in the DFP would dovetail with Reserve Preservation Areas stipulated under the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve. In December, according to the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Clinton’s plans to establish the Reserve were being “viewed with apprehension by the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council.”

Executive Director Simonds was quoted as saying that if the reserve “impacts fisheries in any way, the Council probably won’t be able to support it.”

Further reading

Honolulu Star-Bulletin. 2000. NW Hawaii preserve brings mixed reactions. Tuesday, December 5, 2000. http://starbulletin.com/2000/12/05/news/story6.html.

Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council. Summary. 2001. Draft Environmental Impact Statement, Draft Fishery Plan for Coral Ecosystems of the Western Pacific Region. http://www.wpcouncil.org.

Q39 returns to “Harassment Beach”

David Jordan reports from the Keanae peninsula, Maui

Q39

Monk seal RQ39 returned today (11 February 2001) to the same beach on the Keanae peninsula where she was attacked in August '98 [see The Life & Times of Q39,TMG 1(2): December 1998 and “He didn’t eat the seal, did he?”,TMG 2(1): May 1999]. This was her first return to that particular cove since April '99 as far as I know, and I live across the street so I check it frequently.

She looks very good, quite a bit bulkier than when I saw her last. My estimate would be 400 lbs. and 6.5 to 7 feet in length. She still has both tags. I don't think there are any new scars to report, though I did note a small (3 inch long) patch of black fur on her creamy-yellow underside, just in front of her left front flipper. [Note: Photos suggest that this is indeed a V-shaped new scar probably from a shark encounter. NMFS, meanwhile, reports that “Q39 looks healthy, like she's been finding plenty to eat, and is larger than most seals her age in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.”]

I watched her for 4-5 hours before she returned to the water. During that time, 2 groups of visitors stopped, and I told them the Hawaiian monk seal story. They watched respectfully and left when they had had their fill. Another group of local residents also stopped and observed the seal from their car.

Three other groups of Maui residents also stopped. The first group consisted of 3 men in their late 20s, early 30s. Two of them stayed in the pull-off area (5-10 feet from the seal), while the third crawled down onto the rocks with a disposable camera until his face was probably 12 inches from the seal's face. Luckily for him, she didn't wake up.

Next was an older local man, in his 50s or 60s. He whacked on the coconut tree 5 feet from her with a stick, whistled and yelled in an effort to get her to look up for his pictures.

He was quickly joined by a possibly drunk but definitely hostile man in his mid-late 20s, driving a pickup truck disguised as a boom box with the volume on 9. He parked 10 feet from the seal and opened his door so she could hear the Rap music better. Then he got belligerent with me, ordering me to put my camera away, “where do you live?” etc…

After 5-10 minutes of Gangsta Rap, Q39 had had enough, and she and then I departed.

Q39 was still hanging about the area two days later, and someone (possibly DOCARE – the Department of Conservation and Resources Enforcement) had put Police barrier tape around her immediate vicinity. I was relieved that officialdom had noted her presence and had taken this small step to provide her with a little space to rest.

Q39 returned to her favourite Keanae beach on 11 March just in time to suffer another round of encroachment from the humans. Highlights included large groups of visitors standing next to her posing for pictures and a teenage girl attempting to pet the seal.

This harassment appeared to cause the animal to abandon the beach for the relative safety of lolling in the shore-break (a short-lived solution due to the rising tide and surf conditions) and came at a time when beach rest seemed to be critically needed: Q39 was bleeding from two puncture wounds centrally located on her ventral posterior.

Between the stories I have heard and my own observations of some of the treatment this particular animal has received from humans, gunshot wound or spear stabbing immediately came to mind, but further inspection also revealed what appeared to be a crescent shaped wound, possibly bleeding, on her left dorsal posterior. I will have to wait for the photo evidence, but at this point I surmise that a rather large shark hit from the left and behind, with the upper right jaw leaving the crescent wound just in front of the tail flippers and two lower teeth causing the ventral punctures.

If that scenario is correct, Q39 is fortunate to have escaped far more serious injuries in her latest shark encounter. She was less fortunate that her latest encounter with humans caused her to re-enter the water while still bleeding.

|