|

THE ISLANDS AT THE END OF THE LINE

Exploring the N. Sporades Marine Park

William M. Johnson

|

|

|

|

(click to enlarge)

|

|

Sailing east from the swelling tourist resort of Skiathos, the landfalls become increasingly tranquil and untouched by the modern world. Up ahead, beyond the craggy outlines of Alonissos, lie uninhabited islands whose shores have never known a hotel complex, a pedalo, a souvenir boutique or a disco nightclub. Possibly, they never will. When the President of Greece added his signature to a long-awaited decree in May 1992, the outlying islands of the Northern Sporades archipelago were suddenly transformed into one of the Mediterranean’s most outstanding wildlife sanctuaries.

On a clear day, Alonissos’ higher slopes offer some of the most breathtaking views to be had anywhere in the Aegean. But it’s from a vantage point high on the island’s mountainous spine that the visitor can really begin to appreciate the magnitude of this venture in ecological and cultural preservation. In a sweeping eastern panorama, islands and rocky islets like circling moons, scatter out into the Aegean blueness towards the Park’s outer rim, its boundaries encompassing some 2200 square kilometres. Forested, craggy, or bound by precipitous red cliffs, each island possesses its own distinct identity. Forming a narrow channel with Alonnisos is the low snaking island of Peristera, uninhabited except for the few fishing families who have built a cluster of rickety houses on its western shore. Beyond, a pair of islets known as the Two Brothers form a gateway to rocky Skantzoura. To the northeast loom the graceful contours of Kyra Panaya, its recently restored Byzantine monastery looking out over the rugged outlines of Yura and Prassonisi. Further still, visible through the lingering mist, lies Piperi with its pine-forested crown and cave-riddled cliffs. A few degrees north the Park’s outermost island, Psathura, barely raises its volcanic face from some of the windiest and storm-tossed stretches of the Aegean.

Solitary whales and schools of dolphin migrate through these waters, large stretches of which have been put off-limits to industrial-scale fishing. Species sighted in the area include the common dolphin (Delphinus delphis), striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba) and the long-finned pilot whale (Globicephala melas). Making their ponderous way towards distant nesting sites are also Loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta). The seabed finds extensive Posidonia sea grass meadows, various species of sponge and also the endangered red coral (Coralium rubrum). Among the numerous bird species finding refuge in the Park is the cliff-nesting Eleonora’s falcon (Falco eleonorae) and the red- black- and yellow-billed Audouin’s gull (Larus audouinii), one of the rarest gulls in the world. Rare wildflowers, some endemic to these islands, also take advantage of the absence of human footprints.

But if there is one species that symbolises the Park’s identity, it is the Mediterranean monk seal, Europe’s most endangered marine mammal. Although estimates are hard to come by – both because of the shyness of the species and its mysterious seasonal movements – it is thought that as many as 55 seals may live around these shores. If so, that would make the National Marine Park of Alonissos, Northern Sporades (NMPANS) the species’ largest surviving colony in the Mediterranean.

Of pirates, red wine and dynamite

|

|

|

|

Palaia Chora or “Old Alonissos”

|

|

Though not always content or sure of its role, Alonissos could be described as the capital of the Marine Park archipelago. Some 2800 people live on this mountainous island of dense pine woods, olive groves and pebble shores. Along its wild and wind-torn northern coastline, sheer cliffs plunge into a cobalt sea. Couvouli, its highest peak at 476 metres, is sometimes dusted with snow in winter.

During the Middle Ages the island was known as Liadromia, in classical times as Ikos. At the rust-red cliffs of Kokkinokastro (literally ‘Red Fortress’), archaeologists have unearthed ancient city walls, pot shards, tombstones and graves.

Perched on a precipitous rocky hilltop, 250 meters above the sea, there is Palaia Chora or “Old Alonissos”, a village dating back to the 10th century. The medieval Aegean, it seems, could be a lawless place. The old town’s steep slopes formed a natural fortress against marauding pirates, but it still fell to the raiders. The last pirate to loot the town was reputedly the infamous Barbarossa in the sixteenth century, then acting at the behest of the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire.

Narrow stone-flagged streets wind their way between the two-storey stone houses, scarlet bougainvillaea cascading from wooden balconies. Here and there, ruined, roofless shells of houses can still be seen, a stark and eerie reminder of the earthquake that struck in 1965, virtually destroying the town.

Restoration has proceeded at a lightning pace in recent years, bringing a sudden windfall to Alonissos’ building trade and tourist industry. Foreign cash may have bankrolled the restoration, with Britons, Germans and Italians snatching up the ruins for holiday or retirement homes, but the building effort has remained largely faithful to Alonissos’ historical and cultural identity. Palaia Chora becomes a ghost town in winter, its houses, tavernas and village shops all boarded up. From their deserted terraces on a clear day, even the snowy peak of Mt. Olympus, legendary home of the ancient gods, looms in the distance.

A meandering stone pathway leads down to Patitiri, the island’s port town that is so maligned for its noise and ugliness – even though it possesses a certain indefinable charm that grows on you.

Except for a few poor fishing and trading huts, Patitiri was never an ancient settlement. As towns go, it grew up almost overnight following the 1965 earthquake, which goes some way towards explaining the flat-roofed, concrete-box architecture. Refugees from ruined Palaia Chora flocked to nascent Patitiri. For two long winters they lived in tents, unable to move the authorities to provide grants and loans to repair their houses. When the Colonels seized power in 1967, they decreed that the homeless should be rehoused in a new district in Patitiri. In came the concrete mixers and up went row after row of substandard housing, the legacy of which can still be seen today along the town’s shabby streets.

A visit to the privately-owned Historical and Folklore Museum in Patitiri is to see how markedly things have changed on Alonissos over the last hundred years. Down in the Museum basement, illuminated displays offer windows on a lost world – the crafts and tools of people that, like their sepia daguerreotype portraits, have all succumbed to the inevitability of time. Here’s the smithy, anvil and furnace at the ready to shoe a horse or mule. Here’s the barber’s shop, equally equipped to pull rotten teeth as to razor a three-day stubble. The tailor, the potter, the cobbler, the weaver… you’d be hard-pressed to find any of them now, as the island slides towards Cash ’n Carry mentality like everywhere else.

|

|

|

|

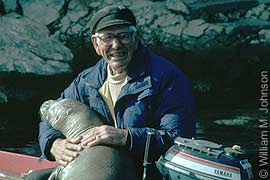

The founder of the Historical and Folklore Museum, Costas Mavrikis, with peasant sandals reputedly of seal skin

|

|

Behind one window there’s a replica of a traditional Alonissos house, complete with rounded fireplace, wooden crib, loom. Slung over coat hooks in a corner are a pair of thonged peasant sandals, believed to be of seal skin. Except for the reminiscences of old men, voices that become fainter year by year, there are few historical records of how local people set about hunting seals. A Dutch map dating back to the 17th century depicts a walrus over a misshapen rendition of Alonissos, suggesting that long ago traders may have visited the Sporades to buy skins and oil.

Up until the early 1950s the island’s main occupation was agriculture, with farming families cultivating barley, maize and grapes over the steep terraced slopes. Alonissos gained fame for its high grade red wines but, in 1953, a virus epidemic struck and the vines began to wilt and die. Within two years virtually every vine on the island had succumbed to disease. Forced to adjust, many farmers turned to fishing, an industry that rapidly established itself as the economic mainstay of the island.

Once a sleepy harbour, Patitiri was gradually transformed into a bustling little port. By the 1970s, some forty caïques were registered to professional fishers on the island.

Few visitors to Alonissos can have equated these graceful wooden boats, capable of reflecting a rainbow of colour into the dark Aegean, with something as sinister as the extinction of an endangered species. And yet for many years these bobbing caïques represented the single greatest threat to the survival of the monk seal.

Like their counterparts throughout the eastern Mediterranean, the traditional fishermen of Alonissos saw the monk seal as a fish-stealing, net-destroying pest, one they would have few qualms about shooting, clubbing to death or even dynamiting given the opportunity. In lashing out at the seal, however, they were actually creating only a convenient scapegoat for their economic woes. As their deteriorating circumstances ultimately forced them to recognise, local fishing grounds were being brought to the brink of collapse not by the handful of seals that survived, but by invading industrial trawlers from distant parts of Greece, and by illegal fishing methods practised by a minority of their own kind – dynamite and chemical fishing, the use of small-mesh nets in fish spawning grounds.

Inflicting the most damage of all was the so-called gri-gri fishery, purse-seine trawlers that fish with gas-fired phosphorescent lights, and nets up to one kilometre long. In their wake, they’d habitually leave a thickening trail of dead fish – non-target species, fish unknown to the marketplace, or young fish too small to sell. According to local fishermen, the trawlers were guilty of dumping several tons of such ‘wastage’ every night, ultimately bringing ruin to fish breeding grounds.

There’d been talk about a Sporades Marine Park as early as 1976, but by 1981 local fishermen had become so frustrated by broken government promises, declining catches and the continuing pillage by trawlers that they took matters into their own hands, threatening to massacre the seals unless they received compensation. To all intents and purposes, the colony was now being held to ransom. With no one expecting the Greek authorities to take action, a small British conservation charity – the Fauna & Flora Preservation Society – launched an emergency public appeal through The Sunday Times. That raised sufficient funds to donate a fish refrigeration unit to the Alonissos Fishing Cooperative. The move proved instrumental in persuading local fishermen that the conservation route was still worth trying. Government and conservation bureaucracies being what they are, however, the Alonissos fishermen were still destined for a long, rough ride. It was not until 1986 that the gri-gri trawlers were at last banned from operating within a 1.5 nautical mile radius of island coasts within the NMPANS.

Odyssia

The research vessel Odyssia undertakes regular research missions into the heart of the Marine Park. The Hellenic Society for the Study & Protection of the Monk Seal – or MOm to use its more recent alias – bought this traditional wooden caïque from a Syros shipyard in 1990 with a grant from the International Fund for Animal Welfare. The organization made its second home in the Sporades the same year and, since then, has played an instrumental role in the founding and operation of the NMPANS, deploying its own fast patrol boat to guard monk seal habitat, and running exhibition centres in Patitiri and Gerakas.

|

|

|

|

Feeding a reluctant orphan in the STRC in Steni Vala

|

|

At the fishing village of Steni Vala, MOm also operates the Mediterranean’s only intensive care station for orphaned monk seal pups, the Seal Treatment and Rehabilitation Centre (STRC). Established with the technical and financial support of the Seal Rehabilitation and Research Centre in Pieterburen, Holland, this small prefabricated cabin has saved several monk seal lives over the last decade.

Most infant seals treated by the rescue unit appear to be the victims of winter storms, possibly being washed out of unsuitable caves by wave surges. The ailing pups are usually discovered on isolated beaches by sympathetic locals who then notify the authorities. After receiving an alert, MOm immediately dispatches its rescue team to the site to examine the pup and administer first aid. Then by ferry, fishing boat, car or plane the weak and shivering pups, carried in wicker baskets and swathed in blankets, are transported to the STRC on Alonissos. When they’re first discovered, the pups are usually suffering from exhaustion, starvation and hypothermia, and are immediately given oral rehydration therapy – a life-saving mixture of water and salts. A few days later, they’re introduced to a nourishing porridge made of minced fish and water. Although force-feeding is necessary initially, the seals gradually learn to eat on their own. Frozen herring – the staple diet for many a marine mammal in captivity – is then introduced to their diet, de-boned in an effort to reduce the risk of digestive complications, to which monk seal pups in captivity are particularly susceptible (MOm expects to substitute locally caught fish in future operations). The aim of the rescue team is to build up the body weight of the foundlings to about 50 kilos to prepare them for their release back into the wild.

|

Did you know?

Rescued monk seals Theo & Dimitri were flown out to Holland for rehabilitation in 1987. They returned to Greece courtesy of an Olympic Airways flight that by chance was also carrying the Minister of Culture and former actress, Melina Mercouri. Illustrating the enduring nature of Greek myths and legends, outraged fishermen voiced their suspicions that Mercouri was having the seals bred en masse in Holland to repopulate the Aegean.

|

Once pronounced fit by the attending veterinarian, tagged for future identification and inoculated against the seal distemper virus, the pups are quickly reunited with the sea. These so-called “cold releases” do not depend on halfway houses to acclimatise the rehabilitated animals to their former wild ways or to teach them how to catch live prey. While such schooling is routinely accorded to more socially complex marine mammals, like dolphins, seals generally demonstrate keener instinctive skills in readaption. The fat reserves that make pups look like bloated balloons on release day act as additional insurance, giving them some breathing space until they’re able to catch their own food. Although the pups often need some coaxing to test the waters, they quickly turn their backs on the anxious humans on the shore that rescued and raised them.

If there was one exception to the rule, it was Theodoros, Alonissos’ most famous monk seal. This Skopelos orphan was the first patient to be treated in the Steni Vala STRC, but returned injured after his first release in 1991, demanding another bout of rehabilitation. It was during this second stint, apparently, that the seal became imprinted on his human nurses.

|

|

|

|

Theodoros: Fisherman's friend

|

|

If you happened to be in the vicinity at the time, it was not exactly the kind of behaviour you’d miss. Theodoros, the supposedly bashful monk seal, could be seen playing with children at the shore, gazing with forlorn guilt at the fishermen mending their seal-damaged nets, stealing beach towels for a more comfortable nap or hopping aboard any convenient dinghy in the harbour to snooze in the sun. In Steni Vala harbour he was even sighted clambering into a rowing boat to lie in the arms of an old fisherman.

Critics can say what they like about rehab science, but Theodoros probably did more to change hostile local attitudes towards his species than any public awareness programme, book, film or leaflet has ever done. His term as monk seal envoy drew to a close in 1993. By then on the brink of sexual maturity, he was already beginning to shun human contact, apparently for the companionship of his own kind. He was last sighted around neighbouring Skopelos, swimming and playing with a larger, adult seal.

Since 1987, 13 orphaned monk seals have undergone rehabilitation – either in Pieterburen or Steni Vala. Of these, 6 have been returned to the protected waters of the Sporades Marine Park and 7 have perished, usually as a result of complications associated with their stranding. While the number of orphans encountered may seem insignificant in conservation terms, supporters of rehabilitation believe that every life counts when a species is teetering on the brink of extinction. (In addition to the pups, the MOm rescue team has also treated six ailing monk seal adults in situ, one of which died).

An ambitious 1992 plan, to construct a dedicated monk seal rescue centre on Alonissos, was subsequently shelved as a result of cost concerns and lack of candidate animals. Contrary to expert opinion at the time – which predicted up to 20 orphaned pups being found every year with an efficient Aegean-wide alert system in place – rescues have been few and far between. MOm’s prefabricated intensive care station, however, is due for replacement. Concluding an agreement with the government, the organisation has taken over the running of the much-maligned Biological Station at Gerakas bay, an EU-funded white elephant that had been standing largely idle for two decades. Exhibition centre, library, and a brand new rehabilitation unit have all been added to the Station, which lies towards the northeast tip of Alonissos, along a dementedly twisting mountain road. There are rumours that Gerakas may one day also be the site of a captive breeding experiment, though MOm is saying little about any such plans at present. A more pressing priority, apparently, is to obtain legal access to the Station. Due to one of those twilight zone oversights to which Mediterranean bureaucracies seem particularly prone, the Athens authorities neglected to purchase any land with their Gerakas plot that might actually allow free access to the outside world. As a result, the Station is now literally fenced in by a single goatherder who remains stubbornly unmoved both by promises of compensation and threats of compulsory purchase.

Stepping stones

In terms of the Marine Park, Alonissos is like the last staging post to the cluster of islands ahead. Once you’ve left the sleepy fishing villages of Steni Vala and Kalamakia behind, you’re entering a world which seems suspended in a different time. And perhaps it is. Tour boats may intrude in summer, but on these, the so-called Deserted Islands, roads, cars, shops, electric current and other modern conveniences appear to belong to a future not yet even imagined.

|

|

|

|

The monastery on Kyra Panaya

|

|

|

Kyra Panaya, with its rounded hills, gentle undulations and olive groves, is still owned by the ancient monastery of Megisti Lavra on the northeastern tip of Mt. Athos, visible on a clear day some 50 miles to the north. Because religious edicts on the Holy Mountain prohibit even the presence of female animals, it was the small tenant farm at Aghios Petros that supplied goat’s cheese to Mt. Athos’ oldest monastery. By 1992, Giorgos and Paraskevoula Georgis were the only human inhabitants on the island, pottering about their vegetable garden, tending their goats and chickens. The farm has since been abandoned – according to some, the victim of Marine Park regulations that penalise not only modern threats but also traditional pursuits.

On a high green bluff on the east coast stands Kyra Panaya’s 18th century monastery – originally founded in the 9th century – its blue bell tower and stone roof looking out over a sweeping expanse of sea and a scattering of islands. Once a safe haven for fishermen marooned by stormy weather, the monastery is also deserted now, its last remaining monk having returned to Mt. Athos almost two decades ago.

Another Byzantine monastery sits atop the island of Skantzoura, a little isolated world encircled by its own islet-moons. Despite unique architectural features, the monastery has fallen into ruin now. According to local legend, it was at some point during the 1960s that the last monk to inhabit the monastery, brother Nimnos, spied a seal fast asleep on the rocky shore and decided that he’d try to catch the animal. On the Holy Mountain, so it is said, monks turned seals into harness leather, shoes, lamp oil and medicine whenever the need or the opportunity arose. So Nimnos, convinced he was onto a bright idea, crept towards the shore with a length of rope, tying his mule to the neck of the sleeping seal. No sooner had he secured the knot – so the story goes – than the seal awoke in panic and scrambled into the sea, dragging the hapless mule with it. As the desperate seal plunged beneath the waves to escape, so the mule frantically thrashed about in the water, barely able to keep its flaring nostrils above the surface. Only when the rope snapped on the crude wooden saddle were the two unfortunate animals spared, the mule scrambling ashore, none the worse for wear, the seal streaking off through the Posidonia, its prejudices about humans probably reaffirmed.

Far more arid and desolate than its neighbour, Yura has little in the way of forest cover or maquis – the myrtles, heaths, arbutus, cork oak, and ilex that traditionally cover Mediterranean coastal hills and mountainsides. Clinging to its steep slopes are other low shrubs that have adapted to the arid soil, bringing a blaze of burnished red and copper to the island in spring. Here and there, the rare Cretan maple can also be found, and in the east, fig trees reputed to reach a height of five metres.

Passing its untamed shores, observant explorers can sometimes catch a fleeting glimpse of the island’s wild goat – according to some, an endemic species related to the Cretan wild goat (Capra hircus aegagrus).

About an hour’s climb from the landing point is the Cyclops’ Cave, its mouth partially hidden by trees. Treacherous underfoot, a trail hewed out of stone spirals its way down into the darkness until at last you reach a large cavern with subtly-shaded stalactites and stalagmites. The cave complex is still largely unexplored but archaeologists have discovered stone and bone tools, including hooks, knives, and pots, dating back to 10000 BC. Despite protests by tour agencies on Alonissos, the Cyclops’ Cave remains strictly off-limits to tourists.

Of the lesser islands in the NMPANS, several are notable for distinctive landmarks. On the tiny islet of Papou, lying between Kyra Panaya and Yura, can be found the remains of yet another monastery, including evidence of terraced gardens where the monks that once lived here – a handful at most – cultivated whatever fruits and vegetables the rocky soil allowed. The little chapel remains intact, if in dire need of repair.

|

|

|

|

The sea daffodil on Psathura

|

|

With its highest point hardly exceeding ten metres, little can be seen when approaching Psathura except for a lonely stone lighthouse, which towers over this tiny dune- and scrub-covered islet lost in a seemingly endless sea.

The lighthouse keepers and their families that once lived here have been superseded by automation; they bade farewell to the island more than a decade ago.

Submerged ruins are said to be visible just off the island’s shores, allowing snorkellers to discover traces of ancient streets and houses – assuming they can ever find their way to this mysterious sunken city.

Along the white, sand-ribbed shore to the south, the fragrant and graceful sea daffodil (Pancratium maritimum) still grows undisturbed. The occasional seal has also been known to emerge from the water here and loaf about in the sun.

Piperi, with its precipitous, brittle and cave-riddled cliffs, forms the heart of the Sporades monk seal refuge. In the translucent light of dusk, the sky becomes flecked with numerous Eleonora’s falcons, the air resounding with their piercing hunting cry. Above, after climbing a steep and treacherous path, you suddenly enter the greenness and almost virginal serenity of the island’s pine forest. There’s few traces of human presence here: the old tin cups nailed to the trees, where Piperi’s owners once tapped the bark for the oozing amber resin that gives retsina its distinctive taste; and higher still, on the crown of the island, another abandoned monastery – a whitewashed chapel with a cupola-shaped stone roof, and a couple of tumbledown houses.

There is no safe anchorage at Piperi, a characteristic that somehow enhances the island’s fortress-like identity. Even fishermen who once dropped anchor here for the night would keep a close watch on the wind and the swell, always on the alert for a sudden change in weather that would send them scuttling towards Yura for shelter.

Here, in the highly protected Red Zone of the Park, the seal caves are strictly out of bounds to all but authorised researchers, and vessels are prohibited from approaching any closer than three nautical miles to Piperi’s coastline.

Odyssia’s researchers use their inflatable boat when cave checks are called for. To keep disturbance to the minimum that the methodology itself allows, the engine is turned off at a distance, the final approach being made with paddles. In cases where the entrance is too narrow or the swell too high, team members swim into the caves.

|

|

|

|

Mounting an automatic camera in a seal cave on Piperi

|

|

|

The monk seal’s acute sensitivity to human disturbance has made potentially invasive scientific research a hot target for those who believe the animals would be far better off just left in peace. In an effort to reduce their own intrusions, MOm researchers have deployed automatic cameras in several seal caves to monitor behaviour and the welfare of individual animals. Funds permitting, they also hope to install infrared-illuminated video cameras that would beam live pictures back to the research station at Gerakas. Cameras mounted at strategic points around the island would also act as a high-tech deterrent to those tempted to enter the Piperi exclusion zone. A plan to establish a warden station on the island, to improve guarding efficiency and allow research from non-invasive observation posts, has been gathering dust for years, another victim of funding constraints and practical difficulties associated with Piperi’s remoteness and forbidding topography.

A mass of raw data has been collected over the past decade, some promising potentially valuable insights into little known aspects of the species’ biology and behaviour. While much of it still waits to be processed, analysed and published – a casualty of more pressing conservation priorities – MOm is convinced that research in monk seal habitat is not a matter of satisfying idle scientific curiosity, but of offering tangible benefits for the long term recovery of the species.

Sometimes, after nightfall, eerie, siren-like cries come echoing across the water from Piperi’s caves, the sound of a female seal in labour or a mother nursing her pup.

Ten years after the establishment of the NMPANS, it seems that more pups are being born at Piperi than at any time in recent history. Lately, infant seals have even been seen huddled together, six to one cave – an astonishing spectacle for those who have been accustomed only to plummeting birth rates and population extinctions [see Baby boom in the Sporades, TMG 3(2): November 2000]. From 1990 to 2000, MOm researchers counted 77 newborn pups in the Park. Good enough reason, you would think, to establish the network of protected areas in the Aegean that has been promised for a quarter century. Sad to say, even proving that the monk seal can be saved from extinction is still not getting through to people in high places – particularly those who find it more convenient to believe that the species is a lost cause.

For further reading, turn to our companion article from the Sporades, All at Sea

|