|

|

|

|

||

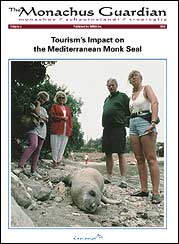

J.J. Wilcox (TMG 3:1, Tourism’s Day in Court) wonders if any type of legal action may be taken against those responsible in the tourism industry for the decline and regional extinction of the Mediterranean monk seal. Re. Surf’s Up, Live! Maui on less than $500 a day – Snapshots and outtakes from the 13th Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals, Maui, Hawaii. While on vacation in southern Spain, I travelled to a cave outside of Ronda (Cueva de la Pileta). Among the old paintings on walls was something that looked like a monk seal. The Spanish guide told me then that there were sightings of monk seals along the rocky coast between Algericas and Tarifa, but also that there were problems. Can you tell me what kind of problems? I understand that the methodology and results can be controversial, but economists have made attempts to place a dollar value on certain endangered species. Would you know if anyone has attempted to do this for the monk seal? What is the current population count of the Mediterranean monk seal (as of 2000)? How is that figure compiled? I am convinced that – with some work and goodwill – advocacy for the Mediterranean monk seal could expand beyond the exclusive range of a very few scientists and other concerned individuals into the larger (and therefore more vocal and powerful) range of the "general public." This could be accomplished without any expense: Environmental Defense (formerly Environmental Defense Fund or EDF) maintains an internet site known as ACTION NETWORK (http://www.actionnetwork.org) and is actually looking for other environmental organizations to join. Having visited the island of Samos in spring 2000, I only realized your information on the island’s monk seals at www.monachus.org when I had returned home. I am writing this letter in response to the Cover Story of The Monachus Guardian 3(1) May 2000 [When Fishermen Save Seals], relating to the entanglement of monk seals in fishing gear as an extinction factor.

Tourism in the Dock

While the tourism industry is represented internationally by such bodies as the World Tourism Organization (WTO) in Madrid and the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) in London, legal realities suggest that court action might be more successful if pursued against government institutions rather than private corporations and their international lobbying groups.

Indeed, the tourism interests that can be implicated in the decline and extinction of the Mediterranean monk seal operate in such a way as to imperil this species and its habitat in part because governments permit them to. It may therefore be reasoned that governments must be held accountable for not restraining the industry from its injurious impact upon the monk seal, and also for not establishing sufficient numbers of properly-guarded sanctuaries for the species.

Official inaction or laxness of this type can represent grounds for effective legal action under EC Directive 9243 of May 1992 (often known as the Habitats Directive).

Following possible delays in implementation negotiated individually by governments, all European Union member states have the obligation to ratify and to transpose into national law, the directive duly adopted by the EC Commission.

If the directive has not been transposed as required within the specified timeframe, a citizen or an organization directly and personally concerned may sue before the EC Commission in application of article 169 of the EC Treaty. This permits the Commission to request from the state concerned the reason for its failure to meet its legal obligations. Should the state continue to default, the EC Commission may refer the case to the EC Court of Justice.

If, on the other hand, the directive has already been transposed into national law as required, but is not being effectively applied, other legal avenues can be pursued. In this case, any citizen or organization directly concerned by ineffective implementation of the law can sue before the court of that country, both to request proper application of the statute and to claim for damages.

Xavier Jacques Bacquet, Avocat à La Cour, Paris

![]() Editor’s note: The Monachus Guardian conveys its thanks to the Bellerive Foundation for commissioning the legal opinion on which this letter is based.

Editor’s note: The Monachus Guardian conveys its thanks to the Bellerive Foundation for commissioning the legal opinion on which this letter is based.

When do you plan to organize a Society of Marine Mammalogy Meeting in your neck of the woods?

Paul Nachtigall, University of Hawaii, USA

Richard Åkesson, Sweden

![]() Editor’s reply: Although effectively extinct in Spain, monk seal stragglers from Algeria and Mediterranean Morocco may make rare appearances in southern Spain. However, most observations in recent years have been around the Chafarinas Islands off Morocco and, to a lesser extent, the remote Isle of Alboran, lying virtually midway between Morocco and Spain. Intentional kills by fishers, accidental entrapment in fishing nets and collisions with boats have all been cited as causes of mortality. Lack of suitably protected and undisturbed habitat is blamed for discouraging the species from naturally recolonising the coasts of southern Spain.

Editor’s reply: Although effectively extinct in Spain, monk seal stragglers from Algeria and Mediterranean Morocco may make rare appearances in southern Spain. However, most observations in recent years have been around the Chafarinas Islands off Morocco and, to a lesser extent, the remote Isle of Alboran, lying virtually midway between Morocco and Spain. Intentional kills by fishers, accidental entrapment in fishing nets and collisions with boats have all been cited as causes of mortality. Lack of suitably protected and undisturbed habitat is blamed for discouraging the species from naturally recolonising the coasts of southern Spain.

Donald Schug, USA

![]() Editor’s note: The Monachus Guardian would like to hear from anyone who can shed further light on this issue.

Editor’s note: The Monachus Guardian would like to hear from anyone who can shed further light on this issue.

Go Figure

Craig Reineke

![]() Editor’s reply: Current population estimates for Monachus monachus range from 379 – 530 individuals. It is, however, a notoriously inexact science. Check out The Numbers Game in the International News section of TMG 3:1.

Editor’s reply: Current population estimates for Monachus monachus range from 379 – 530 individuals. It is, however, a notoriously inexact science. Check out The Numbers Game in the International News section of TMG 3:1.

ACTION NETWORK is composed of many organizations. Periodically I receive emails from the environmental organizations I have registered with, which may, for example, ask me to write, call or email a legislator to urge him/her to vote for a stronger law to defend endangered species, or to ask the president of a company not to build a dam in the Philippines. The great part is, that if (as most times) I choose to contact these persons by email, a previously written email appears on my screen which I may personalise or change as I feel!

I may be idealistic, but if it works for 21 organizations, couldn't it work for a few more, too?

Gian A. Morresi, USA

Now I'm preparing some fact sheets on Samos for friends who will organize hiking tours on the island next year [with each hiking group averaging 12-18 individuals]. My questions:

1. Are the management plans for Seitani as proposed by MOm now being implemented? If not, what is the current state of play?

2. How should hikers behave when coming to Seitani? Or would you recommend not going there?

Peter Merforth, Berlin

![]() Editor’s reply: A Special Environmental Study (SES), on which the management plan for the Seitani area of Samos will eventually be based, is still being developed by a private environmental consultancy firm commissioned by the Samos Prefecture. It will then have to undergo further scrutiny by the local authorities before the plan or any of its proposed measures are adopted. Opposition among certain factions, who would rather see the Seitani area developed for tourism, may further slow the pace towards a full protection that includes effective guarding and monitoring.

Editor’s reply: A Special Environmental Study (SES), on which the management plan for the Seitani area of Samos will eventually be based, is still being developed by a private environmental consultancy firm commissioned by the Samos Prefecture. It will then have to undergo further scrutiny by the local authorities before the plan or any of its proposed measures are adopted. Opposition among certain factions, who would rather see the Seitani area developed for tourism, may further slow the pace towards a full protection that includes effective guarding and monitoring.

Seitani, lying on the northwest coast of Samos, was first declared "Strictly Protected" in 1980 by ministerial ruling, a decision that was eventually validated by Presidential Decree in February 1995. Although the Decree, by implication, strictly prohibits human activities in the core sector, without a management plan to define its structure, Seitani remains in a legal twilight zone. Regardless, the area is also identified as a Natura 2000 site, part of a network of protected areas being established under a European Union conservation plan for endangered species and habitats. MOm, Greece’s leading monk seal conservation NGO, is pursuing the establishment of a number of Natura 2000 areas for the species, including the Fourni Islands-Samos complex, which incorporates Seitani (see TMG, passim). MOm has also provided specific monk seal protection proposals to the consultancy responsible for drawing up Seitani’s management plan. These include two marine zones (200m and 500m wide) with regulations on fishing activities and boat traffic.

The aim of the Network 2000 areas – including Seitani – is to provide undisturbed habitat for a species that, in large part, is facing extinction precisely because of human harassment, persecution and disturbance. While it is unclear at present whether the Seitani management plan will allow public access – and if so, to what extent – people venturing into monk seal habitat anywhere should take the following precautions:

In your article, you argue that "…incidental entanglement in fishing gear [is] considered a major threat contributing to the overall decline of the species…" Although I do not disagree that accidental capture in nets is a threat for the endangered monk seal population in the Eastern Mediterranean, this threat should be put in its proper perspective, based on the most recent scientific evidence available.

In support of your argument you present abundant evidence from several regions of the species’ range. However, most of this work was conducted during past decades and almost all of it was based on fishermen’s or layperson’s reports. I would like to draw your attention to our recent article, Causes of Mortality in the Mediterranean Monk Seal in Greece (Androukaki et al. 1999. Contributions to the Zoology & Ecology of the Eastern Mediterranean Region 1(1999): 405-411), that for the first time addresses the causes of death in this species through direct evidence from necropsies rather than from anecdotal reports from fishermen.

Although our paper does cite accidental death by entanglement in fishing gear as a mortality factor, it is by no means one of the main threats to the species. Unfortunately, deliberate killing remains the main source of mortality, accounting for 43% of the deaths of adult/juvenile animals. Natural mortality is high, accounting for 91% of the pups found dead. Accidental deaths in fishing gear account for the 12% of the total deaths recorded. All animals found dead by drowning in fishing nets are juveniles ranging from 1.5 - 4 years old. It therefore seems that this is also the most vulnerable section of the population. This could be explained by the fact that these animals, although able to live independently, are not as strong and skilful as the adults. Lacking experience, they are less cautious when collecting fish from static nets and therefore risk entanglement.

Fortunately, in Greece, licenses were never issued for driftnets, which are far more harmful than traditional static nets for marine mammals.

In a strategy based on experience and the results of scientific research, MOm has concentrated its efforts on the protection of the monk seal’s main breeding sites in the Aegean and Ionian seas. Our projects here include sensitizing the general public and persuading fishermen not to kill the seals (also using compensation measures, continuous patrolling in the protected areas, and proposing to the government sustainable management of fish stocks).

The example of the National Marine Park of Alonnissos, Northern Sporades is encouraging, where combined efforts in field research, sensitization of the public, compensation and continuous patrolling of the protected area, have furnished positive results. No deliberately killed seal has been recorded over the last 10 years, while the monk seal population appears to be stable. Although the traditional fishery with static nets and longlines is still permitted in the Park (except in the core zone), no incidents of seals drowning in nets have been reported, although this possibility cannot be excluded.

The application of the same rationale to Kimolos in the Cyclades and Northern Karpathos in the Dodecanese, areas recently confirmed as important monk seal breeding sites, will lead to the establishment of a network of protected areas in the Greek archipelago. The achievement of this too long awaited goal provides us with hope for the effective conservation of the most important population of the species.

Jeny Androukaki, Rehabilitation Program Co-ordinator, MOm, Athens.

The editor reserves the right to edit letters for the sake of clarity and space

Copyright © 2000 The Monachus Guardian. All Rights Reserved